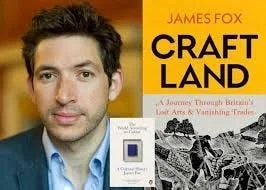

Tamara Cincik's Q&A with Craftland Author James Fox

SHORTLISTED FOR WATERSTONES BOOK OF THE YEAR & SHORTLISTED FOR THE NERO BOOK AWARDS NON-FICTION AWARD 2025, SUNDAY TIMES BOOK OF THE WEEK

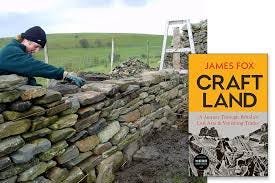

Britain was once a flourishing craft land. For many generations what we made with our hands shaped our identities, built our communities, and defined our diverse regions. Craftland by James Fox, chronicles the vanishing skills and traditions that used to govern every aspect of life on these shores. I interviewed James about Craftland to learn more about why he believes we are seeing a Great British Craft Revival in Britain.

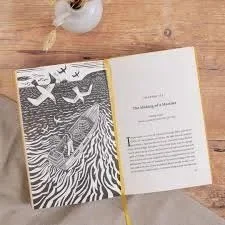

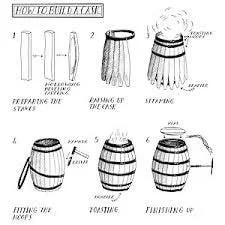

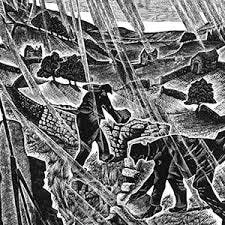

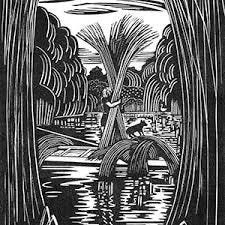

Travelling the length of Britain, from down to the Scilly Isles right up to the Scottish Highlands, James Fox seeks out the country’s last remaining master craftspeople. Stepping inside the workshops of blacksmiths and wheelwrights, cutlers and coopers, bell-founders and watchmakers, we glimpse not only our past, but another way of life: one that is not yet lost and whose wisdom could shape our future. About the author, James specialises in 20th-century art and is Director of Studies in History of Art at Emmanuel College, Cambridge and Creative Director of the Hugo Burge Foundation, which is in their own words, “a major new charity dedicated to supporting the arts, crafts and creative industries across the United Kingdom. We believe that creativity has the power to transform people’s lives and communities, and aim to advance its cause in various ways.”

In Craftland’s publishers Penguin’s words, “For as long as there are humans, there will be craft. It is all around us, hiding in plain sight, enriching even the most modest things. And in this increasingly digital age, it is perhaps more valuable than ever. Craftland is a celebration of that deeply necessary connection between our creative instincts and the material world we inhabit, revealing a richer and more connected way of living.”

Happy reading, I hope you enjoy this Q&A. Please share your thoughts and comments.

Tamara.

1) I loved reading Craftland, which is totally grounded in your travels across Britain. What made you write the book and could you please describe how in your thinking a location shapes the resilience, relevance and value of craft today, both creatively and economically.

British people are pretty down on the UK at the moment, especially if they live outside the wealthy south-east. I wanted to show that the country is still full of creativity and ingenuity, and that every region has its own genius. Craft is absolutely part of that. Harris Tweed, for instance, employs hundreds of people in the Hebrides. It is now the largest single private-sector employer in the Western Isles, generating millions for the local economy while being a source of great local pride.

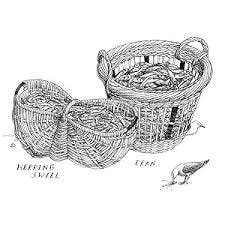

2) I particularly felt drawn to the chapter speaking about High Wycombe and its importance in chair making. How does an area become known for a particular craft, other than the obvious: accessibility to a raw material, say willow?

There are a few reasons, as you suggest. Access to materials is crucial. Sheffield, for instance, emerged as a great metalworking centre because it had plentiful supplies of firewood, iron ore and gritstone, as well as fast-moving rivers that drove grinding wheels. But there are other, more mysterious causes of such specialisms. In the case of High Wycombe, it was also about expertise: about a critical mass of skill and knowledge forming in a particular place and snowballing over time.

3) Clearly there is a growing revival in certain craft skills. Why do you think that is?

There definitely is. I think this is partly the result of a growing awareness of craft, thanks to the advocacy of organisations such as Heritage Crafts and TV programmes like The Repair Shop. It’s also because we are living through a period of crisis and anxiety, which is pushing many people towards the inherently reassuring process of making things by hand.

4) Natural fibres and textiles such as wool, built Britain’s economy. How do traditional textile crafts specifically fit into your thinking on craft, place, and heritage?

Textiles are a central part of our heritage and identity. You only need look at our language. Every time we ‘cotton on’ to something, ‘reel off’ some facts, feel ‘hemmed in’, hang ‘on tenterhooks’, ‘line our pockets’, laugh ourselves into ‘stitches’, tell a windbag to ‘put a sock in it’, call a coward a ‘wet blanket’, or label an unmarried woman a ‘spinster’, we are referring to the manufacturing of textiles.

5) What lessons can the fashion and textile sectors draw from the craftspeople you met for Craftland, in terms of place based skills?

The mainstream fashion sector has long been engaged in a race to the bottom: the goal being to produce the cheapest possible products for the largest number of consumers. But a consumers are increasingly aware of the social and environmental costs of fast fashion, and are prepared to spend more on garments that have been carefully made with natural materials in sustainable ways. If the fashion sector channelled a little bit more of the spirit of craft, they may be surprised by the

6) If you were PM for a day, which policies would you like to see to better support place-based craft? Thinking also outside the South East with more power to the devolved governments.

I’d be a terrible PM (I procrastinate far too much), but when it comes to supporting craft, my wish-list would contain: 1. a root-and-branch overhaul of the education system, from Early Years to Adult Education, with arts and creativity at its heart; 2) a generous system of Living Heritage grants and subsidies to support businesses and individuals promoting vernacular and regional practices and traditions; 3) the creation of a Living National Treasures scheme whereby Britain’s leading makers receive State funding to promote and pass on their skills.

7) How can storytelling and cultural recognition help us to elevate undervalued craft skills within contemporary creative industries? Thinking of UNESCO’s intangible cultural heritage, DCMS now working more closely with Heritage Craft, and JW Anderson’s recent shop opening, showcasing his clear love for British crafts.

I was recently discussing this very issue with Jonathan Anderson himself! He and others like him prove that craft doesn’t need to be fusty and provincial. Well-made things can reach a huge, modern, international market, provided the storytelling is done right. I believe that partnerships between individual craftspeople and bigger brands are a really important part of the sector’s future.

8) Craft is working class art, discuss.

I’m very struck by this phrase but I’m not sure it’s quite right. It’s certainly true that historic distinctions between Fine Art and Craft have been informed by all kinds of social prejudices, particularly against women and the working class. But I think these two practices have much more in common than we often assume. I’ve come to the conclusion that art and craft live within each other, and in all social groups — both being products of the innate human inclination to create things.

9) What would a Great British Craft Revival look like?

We’re living through one. Craft is booming in Britain right now, and certainly has been since the pandemic. Many old crafts are resurgent and new ones being born. I suspect that the AI revolution is only going to catalyse that process.

10) What’s next for you in 2026?

Too much. I’ll continue my teaching and charity work, as usual. I’m also starting a new podcast, which is due to be released in February. And, of course, I’m mulling over a follow-up to Craftland!

Craftland is BBC Radio 4’s Book of the Week this week. Listen to Craftland here.